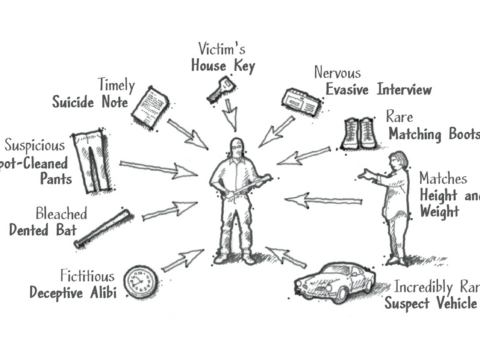

Evidence typically falls into two broad categories. Direct evidence is evidence that can prove something all by itself. In California, jurors are given the example of a witness who saw that it was raining outside the courthouse. Jurors are instructed, “If a witness testifies he saw it raining outside before he came into the courthouse, that testimony is direct evidence that it was raining.” This testimony (if it is trustworthy) is enough, in and of itself, to prove that it is raining. On the other hand, circumstantial evidence (also known as indirect evidence) does not prove something on its own, but points us in the right direction by proving something related to the question at hand. This related piece of evidence can then be considered (along with additional pieces of circumstantial evidence) to figure out what happened. Jurors in California are instructed, “For example, if a witness testifies that he saw someone come inside wearing a raincoat covered with drops of water, that testimony is circumstantial evidence because it may support a conclusion that it was raining outside.” The more pieces of consistent circumstantial evidence, the more reasonable the conclusion. If we observed a number of people step out of the courthouse for a second, then duck back inside, soaked with little spots of water on their clothing, or saw more people coming into the courthouse, carrying umbrellas, and dripping with water, we would have several additional pieces of evidence that could be used to make the case that it was raining. The more cumulative the circumstantial evidence, the better the conclusion.

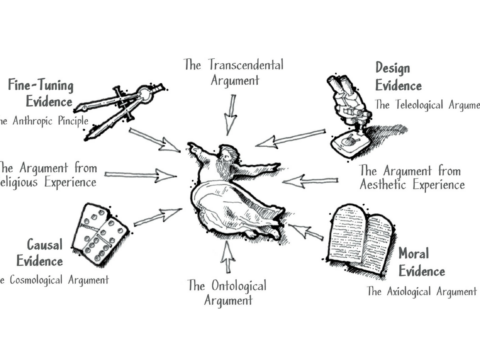

Most people tend to think that direct evidence is required in order to be certain about what happened in a given situation. But what about cases that have no direct evidence connecting the suspect to the crime scene? Can the truth be proved beyond a reasonable doubt when all the evidence we have is circumstantial? Absolutely. Jurors are instructed to make no qualitative distinction between direct and circumstantial evidence in a case. Judges tell jurors, “Both direct and circumstantial evidence are acceptable types of evidence to prove or disprove the elements of a charge, including intent and mental state and acts necessary to a conviction, and neither is necessarily more reliable than the other. Neither is entitled to any greater weight than the other.” Juries make decisions about the guilt of suspects in cases that are completely circumstantial every day, many cold-case homicides have been successfully prosecuted with nothing but circumstantial evidence. Remember, circumstantial cases are powerful when they are cumulative. The more evidence that points to a specific explanation, the more reasonable that explanation becomes (and the more unlikely that the evidence can be explained away as coincidental).

Circumstantial evidence has been unfairly maligned over the years; it’s important to recognize that this form of evidence is not inferior in the eyes of the law. In fact, there are times when you can trust circumstantial evidence far more than you can trust direct evidence. Witnesses, for example, can lie or be mistaken about their observations; they must be evaluated before they can be trusted.

Circumstantial evidence, on the other hand, cannot lie; it is what it is. You and I have the ability to assess and make an inference from the circumstantial evidence using our own reasoning power to come to a conclusion.

Circumstantial evidence is powerful if it is properly understood.

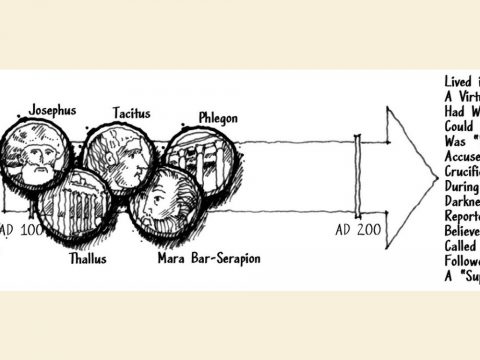

When defending our belief in the existence of God, the resurrection of Jesus, or the validity of the Christian worldview, we may need to take some time to explain the nature, role, and power of circumstantial evidence.

All of us need to respect the power and nature of circumstantial evidence in determining truth so that we can be open to the role that circumstantial evidence plays in making the case for Christianity.

When discussing evidence with skeptics, we don’t need to concede that a particular fact related to the Christian worldview is not a piece of evidence simply because it is not a piece of direct evidence. Even though a particular fact may not have the individual power to prove our case in its entirety, it is no less valid as we assemble the evidence. When we treat circumstantial evidence as though it is not evidence at all, we do ourselves a disservice as ambassadors for the Christian worldview.

J. Warner Wallace. Cold-Case Christianity: A Homicide Detective Investigates the Claims of the Gospels.