The problem of induction—has been a key philosophical challenge, particularly highlighted by David Hume. The inductive principle states that past experiences provide a rational basis for expecting future occurrences to follow the same patterns. However, there are strong philosophical critiques against it:

1. The Circularity of Induction

The most fundamental critique of induction is that it is self-referential and circular. The justification for induction relies on the assumption that past patterns reliably predict future events. However, this assumption itself is based on past experience, meaning that using induction to justify induction is a logical fallacy.

- Example: If we argue that the sun will rise tomorrow because it has always risen in the past, we are assuming that the future must resemble the past—which is precisely the point in question.

2. Hume’s Problem of Induction

David Hume argued that there is no logical necessity linking past observations to future events. Just because something has happened repeatedly in the past does not logically entail that it must happen again.

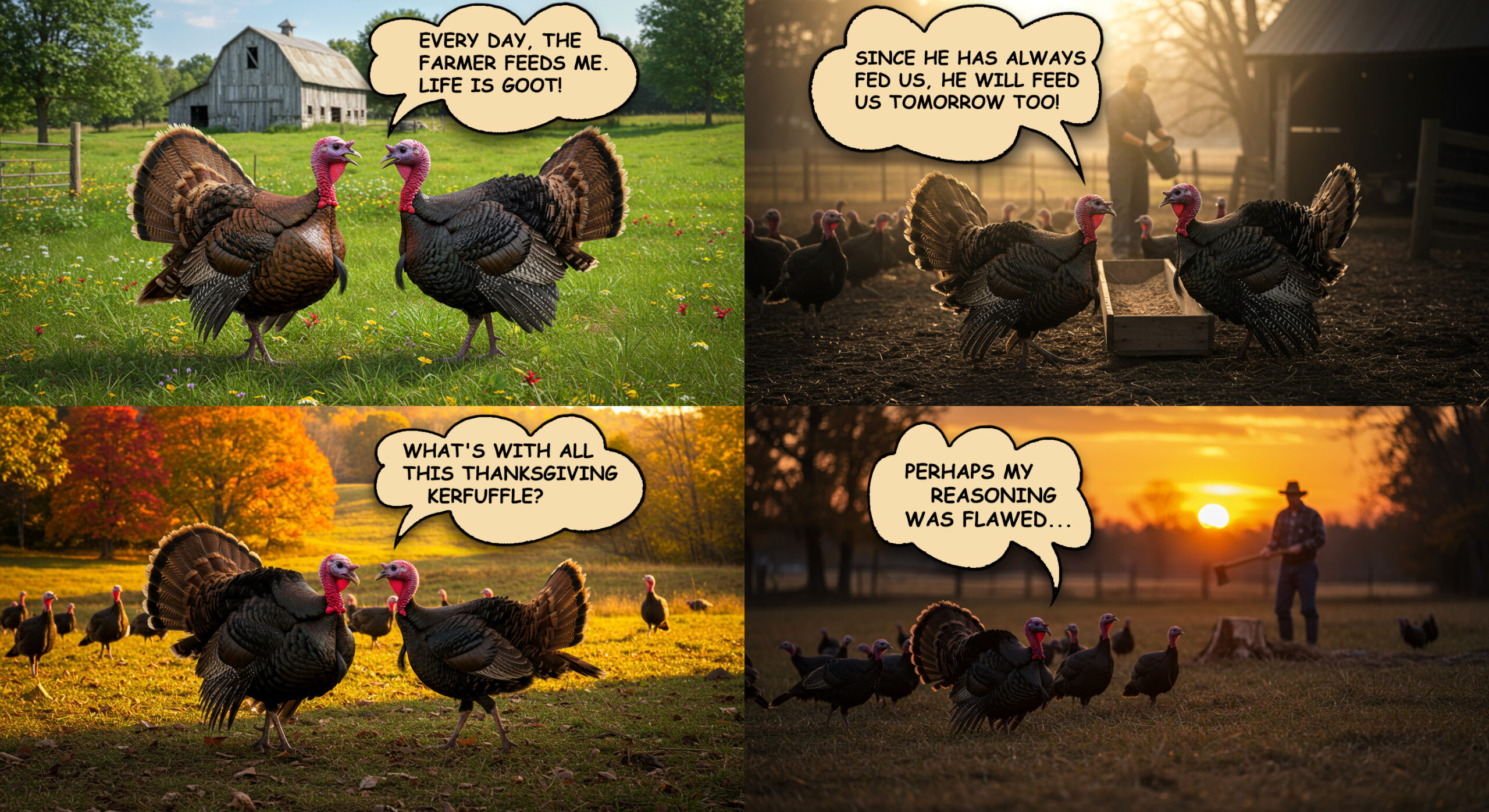

- Example: A turkey that is fed every day by a farmer may expect, based on past experience, that it will continue to be fed. However, this expectation is shattered when Thanksgiving arrives, and the farmer slaughters it.

Thus, induction does not provide certainty, only habits of expectation

3. Induction Is Not A Priori Certain

Unlike deductive reasoning, where conclusions necessarily follow from premises (e.g., in mathematics or formal logic), inductive reasoning does not guarantee truth. Even if something has happened a million times, it does not follow with necessity that it will happen again.

- Example: The law of gravity has been observed to hold consistently, but there is no logical proof that it must continue to do so tomorrow. It is only an assumption based on experience.

4. The Underdetermination Problem

Inductive reasoning often leads to multiple, equally plausible conclusions. This is known as the problem of underdetermination.

- Example: Suppose we observe that all swans we have seen are white. Induction suggests that “all swans are white” is a reasonable conclusion. However, the discovery of black swans in Australia falsifies this conclusion. The problem is that an infinite number of other generalizations could also fit past observations.

5. The Challenge from Skepticism

Since induction lacks a firm rational foundation, skepticism follows naturally. If we cannot justify induction, then much of what we call “scientific knowledge” is not based on reason, but on habit and psychological expectation.

- Example: Suppose we heat water to 100°C and observe that it boils. A strict skeptic might argue that we have no reason to assume it must boil at 100°C tomorrow because our justification is purely based on past occurrences.

6. Alternative Explanations for Apparent Regularity

If induction is unjustifiable, why do we experience regularity in nature? Some argue that the apparent consistency in the world is not a function of induction but of the preconditions of human experience (as in Kantian epistemology) or divine providence (as in theological accounts).

- Example: The laws of physics appear stable not because induction is reliable, but because the universe is governed by a rational, divine order.

Conclusion

The inductive principle, while useful, lacks rational justification. It assumes the very thing it tries to prove, is vulnerable to skeptical objections, and does not provide certainty. While induction is a pragmatic tool for science and daily life, its philosophical foundation remains weak.

—ChatGPT AI