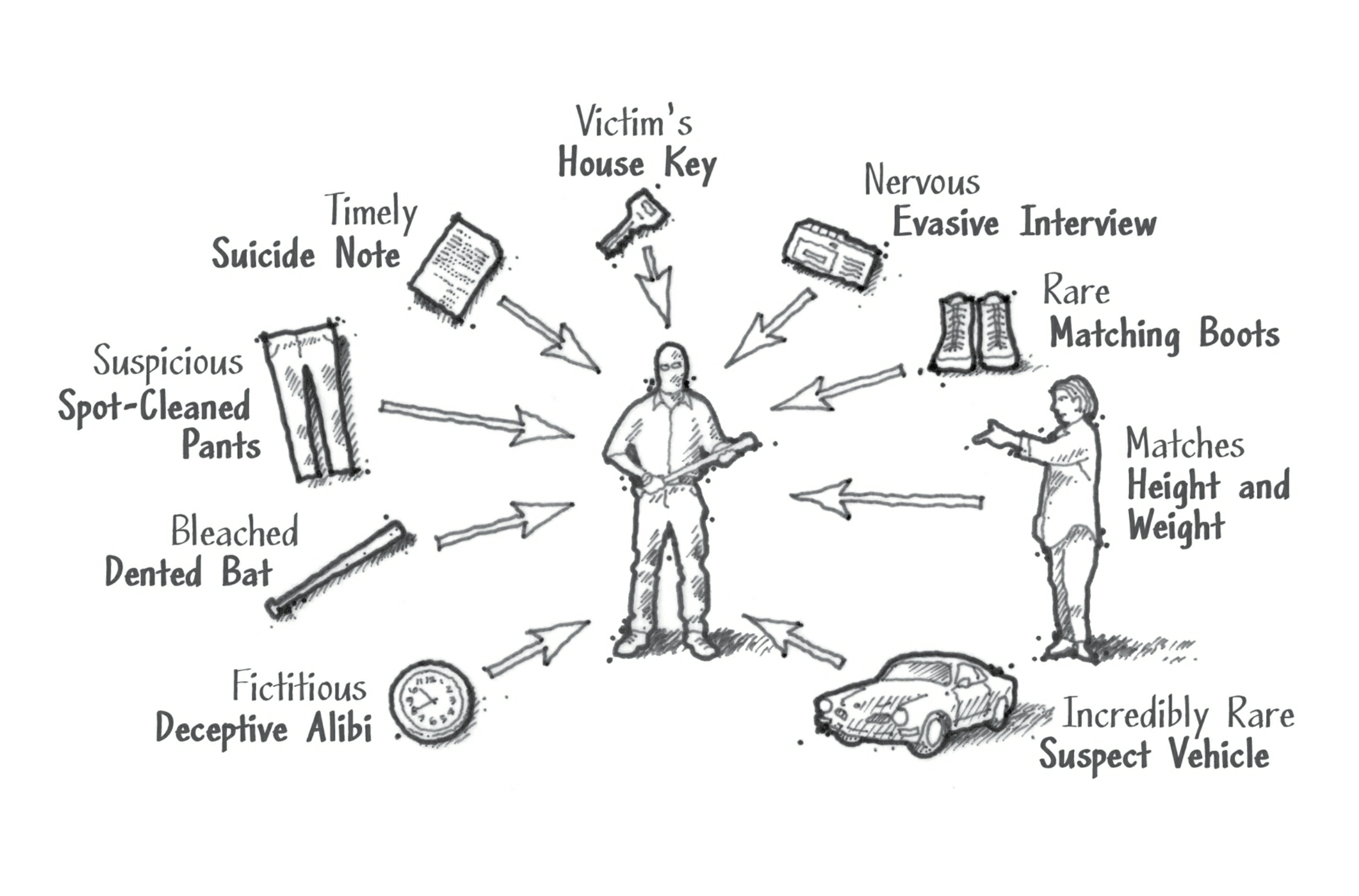

Let’s examine a hypothetical murder to demonstrate the power of direct and circumstantial evidence. I want you to put yourself on the jury as the following case is being presented in court. First, let’s lay out the elements of the crime. On a sunny afternoon in a quiet residential neighborhood, the calm was broken by the sound of screaming coming from a house on the corner. The scream was very short and was heard by a neighbor who was watering her lawn next door. This witness peered through the large picture window of the corner house and observed a man assaulting her neighbor in the living room. The man was viciously bludgeoning the victim with a baseball bat. The witness next saw the suspect open the front door of the house and run from the residence with the bloody bat in hand; she got a long look at his face as he ran to a car parked directly in front of the victim’s residence.

If this witness was now sitting on the witness stand, testifying that the defendant in our case was, in fact, the man she saw murdering the victim, she would be providing us with a piece of direct evidence. If we came to trust what this witness had to say, this one piece of direct evidence would be enough to prove that the defendant committed the murder. But what if things had been a little bit different? What if the suspect in our case had been wearing a mask when he committed the murder? If this were the case, our witness would be unable to identify the killer directly (facially) and would be able to provide us with only scant information. She could tell us about the killer’s general build and what kind of clothing he was wearing, but little more. With this information alone, it would be impossible to prove that any particular defendant was the true killer.

Now, let’s say that detectives developed a potential suspect (named Ron Jacobsen) and began to collect information about his activity at the time of the murder. When detectives questioned Ron, he hesitated to provide them with an alibi. When he finally did offer a story, detectives investigated it and determined that it was a lie. On the basis of this lie, do you think Ron is guilty of this murder? He fits the general physical description offered by the witness, and he has lied about his alibi. We now have two pieces of circumstantial evidence that point to Ron as the killer, but without something more, few of us would be willing to convict him. Let’s see what else the detectives were able to discover.

During the interview with Ron, they learned that he had recently broken up with the victim after a tumultuous romantic relationship. He admitted to arguing with her recently about this relationship, and was extremely nervous whenever detectives focused on her. He repeatedly tried to minimize his relationship with her. Are you any closer to returning a verdict on Ron? He fits the general description, has lied about an alibi, and has been suspiciously nervous and evasive in the interview. It’s not looking good for Ron, but there may be other reasonable explanations for what we’ve seen so far. Even though we have three pieces of circumstantial evidence that point to Ron’s involvement in this crime, there still isn’t enough to be certain of his guilt.

What if I told you that responding officers found that the suspect in this case entered the victim’s residence and appeared to be waiting for her when she returned home? There were no signs of forced entry into the home, however, and detectives later learned that Ron was one of only two people who had a key to the victim’s house, allowing him access whenever he wanted. Ron certainly seems to be a “person of interest” now, doesn’t he? Ron matches the general description, has lied to investigators, is nervous and evasive, and had a way to enter the victim’s house. The circumstantial case is growing stronger with every revelation.

What if you learned that the investigators were approached by a friend of Ron’s who found a suicide note at Ron’s house? This note was dated on the day of the murder and described Ron’s desperate state of mind and his desire to kill himself on the afternoon that followed the homicide. Ron apparently overcame his desire to die, however, and never took his own life. The fact that Ron was suicidal immediately following the murder adds to the cumulative case against him, but is it enough to tip the scales and convince you that he is the killer? It was certainly enough to motivate the detectives to dig a little deeper. Given all this suspicious evidence, a judge agreed to sign a search warrant, and detectives served this warrant at Ron’s house. There they discovered a number of important pieces of circumstantial evidence.

First, they discovered a baseball bat hidden under Ron’s bed. This bat was dented and damaged in a way that was inconsistent with its use as a piece of sporting equipment, and when the crime lab did chemical tests, detectives learned that while the bat tested negative for the presence of blood, it displayed residue that indicated it had been recently washed with bleach. In addition to this, investigators also discovered a pair of blue jeans that had been chemically spot cleaned in two areas on the front of the legs. Like the bat, the jeans tested negative for blood but demonstrated that some form of household cleaner had been used in two specific areas to remove something. Finally, detectives recovered a pair of boots from Ron’s house. The witness described the boots she saw on the suspect and told responding officers that these boots had a unique stripe on the side. The boots at Ron’s house also had a stripe, and after some investigation with local vendors, detectives learned that this unusual brand of boot was relatively rare in this area. Only two stores carried the boot, and only ten pairs had been sold in the entire county in the past five years. Ron happened to own one of these ten pairs.

There are many pieces of circumstantial evidence that now point to Ron as the killer. He had access to the victim’s house, lied about his activity on the day of the murder, behaved suspiciously in the interview, appeared suicidal after the murder, and was in possession of a suspicious bat matching the murder weapon, a pair of questionably spot-cleaned pants, and a set of rare boots matching the suspect’s description. At this point in our assessment, I think many of you as jurors are becoming comfortable with the reasonable conclusion that Ron is our killer. But there is more.

Our eyewitness at the crime scene observed the suspect as he ran to his getaway car, and she described this car to the detectives. The witness believed that the suspect was driving a mustard-colored, early ’70s Volkswagen Karmann Ghia. When executing the search warrant at Ron’s house, detectives discovered (you guessed it) a yellow 1972 Karmann Ghia parked in his garage. After examining the motor vehicle records, they discovered that there was only one operational Karmann Ghia registered in the entire state.

Is Ron the killer? Given all that we know about the crime, the only reasonable conclusion is that Ron is the man who committed the murder. Is it possible that Ron is just unlucky enough to suffer from an unfortunate alignment of coincidences that make him appear to be guilty when he is not? Yes, anything is possible. But is it reasonable? No. Everything points to Ron, and when the evidence is considered cumulatively, Ron’s guilt is the only reasonable conclusion. While there may be other explanations for these individual pieces of evidence, they are not reasonable when considered as a whole. Remember that as a juror, you are being asked to return a verdict that is based on what’s reasonable, not what’s possible.

Our case against Ron is entirely circumstantial; we don’t have a single piece of forensic or eyewitness evidence that links him directly. These are the kinds of cases I assemble every year as I bring cold-case murderers to trial. The case against Ron is compelling and overwhelmingly sufficient. If you, as a juror, understand the nature and power of circumstantial evidence, you should be able to render a guilty verdict in this case.

Wallace, J. Warner. Cold-Case Christianity: A Homicide Detective Investigates the Claims of the Gospels.