In theology, attempts have been made to arrange all these testimonies, which bear witness to the nature and history of God’s existence and being, and to divide them into a number of groups. Thus, over time, we have come to speak of six proofs for the existence of God.

Firstly, the world, however great and powerful it may be, still bears the testimony everywhere that it exists in the forms of space and time, that it has a finite, accidental, dependent character, and thereby points back from itself to an eternal, necessarily existing, independent being, which is the final cause of all things (cosmological proof).

Secondly, everywhere in the world, in its laws and orders, in its unity and harmony, in the organization of all its creatures, exhibits a purpose which makes a mockery of all explanations on the basis of chance and leads us to recognize an all-wise and all-powerful being which has established that purpose with an infinite intellect and which pursues and achieves it through its omnipotent and omnipresent power (teleological evidence).

In the third place, there is in the consciousness of all people contains the awareness of a supreme being, above whom nothing higher can be conceived, and which at the same time is thought by all to be self-existent . If such a being did not exist, the highest, most perfect and necessary thought would be an illusion, and man would lose faith in the testimony of his own consciousness (ontological proof).

This is immediately followed by the fourth proof: man is not only a reasonable, but also a moral being. In his conscience he feels bound by a law that stands high above him and demands his unconditional obedience; and that such a law presupposes a holy and righteous law-giver who can preserve and destroy (moral proof).

To these four proofs come two more, taken from the similarity of the peoples and from the history of mankind. It is a remarkable phenomenon that there are no nations without religion. Some have claimed otherwise, but historical research has increasingly proved them wrong; there are no atheistic tribes or peoples. This phenomenon is of great significance; for its absolute generality demonstrates its necessity and thus confronts us with one of these two conclusions: that either mankind as a whole suffers from a foolish imagination on this point, or that the knowledge and service of God, which exist in corrupted forms among all peoples, is based on His existence.

All these so-called proofs have no power to compel a man to believe. Besides, in science there are few proofs that are capable of this. In the formal sciences, thesis and logic, this may be the case; but as soon as we come into contact with real phenomena in nature and even more so in history, all kinds of objections can usually be made to the reasoning and decisions based thereon. In religion and morality, in law and beauty, whether or not a person will surrender to conviction depends much more on his state of mind. The fool can, in spite of all testimonies, keep saying in his heart: there is no God, Ps. 14:1, and the Gentiles, although knowing God, have not glorified or thanked Him, Rom. 1:21. The above mentioned proofs for the existence of God do not address man as a mere human being, but they address him as a reasonable and moral being. They do not appeal only to man’s analytical and reasoning mind, but they also appeal to his heart and mind, to his reason and conscience. And then they have value, strengthen faith and confirm the bond between God’s revelation outside of man and His revelation in man.

The revelation of God in nature and in history could have no effect upon man if there were not something in man himself that responded to it. The beauty in nature and art could not give man any pleasure unless he already had a sense of beauty in his bosom. The law of morality would not resonate with him unless he himself heard the voice of conscience within. The thoughts that God embodied in the world through His Word would be incomprehensible to him if he were not himself a thinking being. And likewise, the revelation of God in all the works of His hands would be unknowable to man if God had not implanted in his soul an inextinguishable awareness of his existence and being. But now it is an undeniable fact that God has added to the external revelation in nature an internal revelation in man himself. The historical and spiritual studies of religion show again and again that religion cannot be explained without such an inborn awareness; always they return in the end to the often rejected proposition that man is a religious being by nature.

Scripture raises this beyond all doubt. After God had made all things, He created man, and in that same instant created him in His image and likeness, Genesis 1:26. Man is God’s race, Acts 17:28. Although he, like the lost prodigal son in the parable, has left his father’s house, and even in his most distant straying, he still retains the memory of his origin and destination. In his deepest fall he still retains some small remnants of the image of God, after which he was created. God reveals Himself outside of man; He also reveals Himself within man. He does not leave Himself without witness in the heart and conscience.

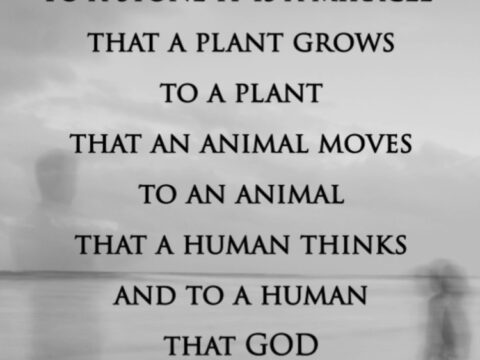

This revelation of God is not to be regarded as a second, entirely new revelation, supplementing the first. It is not an independent source of knowledge apart from the other. It is rather a capacity, a susceptibility, an urge to notice God in His works and to understand His revelation. It is a consciousness of the Divine within us, which enables us to perceive the Divine outside us, just as the eye enables us to see light and colors, and the ear enables us to hear sounds. It is, as Calvin called it, a sense of Divinity, or, as Paul described it, an ability to see the unseen things of God, namely His eternal power and godhead, among the visible things of creation.

Herman Bavinck. Magnalia Dei.